Americans, including subway riders, are significantly bigger than when current rider space guidelines were established. My impression is that more people are bringing suitcases and backpacks into the subway. I have observed more people wearing puffy jackets. Also, it has been noted that, in crowded conditions of mixed genders, women tend to fold their arms in front, expanding the body space that they occupy.[2] No wonder subway trains seem more crowded. Therefore, the rider space and railcar capacity guidelines should be reevaluated in determining the capacity of railcars for the Interborough Express (IBX) line and other purchases of NYC Transit subway cars.

In this article, I discuss the growth in body size of Americans and subway car capacity guidelines.

Riders Are Bigger

Although there does not appear to be much recent published data about the space occupied by a rider, increases in body weight and Body Mass Index (BMI) over the past 65 years indicate that the occupied space has increased significantly.

Statistics collected by the Center for Disease Control (CDC) in a series of multi-year studies, indicate the steady increase over time of mean weights for American men and women. (See table below).[3] Recent data is not readily available, so I have provided a projection for 2025).

Of course, half of the persons in each study weighed more than the mean values reported above. For example, the 2015-2018 study reported that 10% of men weighed over 263 pounds and 10% of women weighed over 232 pounds.[4]

Body Mass Index (BMI) has similarly increased. (BMI is calculated as a person’s weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.)[5] CDC statistics in the multi-year studies indicate the following mean BMI for men and women as follows:[6]

Not only has the mean BMI increased, but a study made in 2021-2023[7] indicated that the percentage of the adult population whose BMI falls in the category of obese (BMI > 30) had increased to 40.3% and those who were severely obese (BMI > 40) had increased to 9.5%. In addition to addressing the general increase in the size of riders, rider space and railcar capacity guidelines should also consider the large number of people with these conditions .

NYC Transit Railcar Capacity Guidelines

The space available for each rider at the peak occupancy of a railcar is dependent on the transit agency’s “loading standards,” which help the agency determine the frequency and number of railcars required at peak periods. NYC Transit has quite sophisticated “Rapid Transit Loading Guidelines” (hereinafter “Guidelines”—copy attached), formally established in February 1988,[8] which are explained in a “Policy/Instruction” (P/I) for “Implementation of Rapid Transit Loading Guidelines,” dated February 2017 (hereinafter “2017 Policy”—copy attached).

In simple terms, the “scheduled loading” of a railcar in the Guidelines is based on the intended maximum number of riders on a train at a Peak Load Point, which is the location along a subway line where passenger loads on trains are the highest in a one direction during a day. The Guidelines and 2017 Policy provide guidance in scheduling trains to avoid exceeding the scheduled loading, which is based on the number of seats and standing space.

In this article, I focus on A Division railcars, which have substantially the same width as the railcars likely to be used on the IBX line, and—therefore—are likely to have similar capacity and crowding considerations. According to the guidelines, these 51-foot long cars can seat 40 passengers, and “At the maximum loading point the Guidelines provide for scheduling 110 passengers per car for the ‘A’ division 51 foot car. Actual observed loads show that this car can accommodate as many as 165 passengers.”[9] (With 40 seated passengers, the 125 standees would share 208 square feet of standing room (see below), having only1.66 square feet of standing space each. That is a so-called “crush” condition.)

In discussing the previous, unofficial standards, the Guidelines’ Technical Appendix said:

The available standing space … is the summation of the space in front of the seats (allowing 6" for kneeroom), which computed by multiplying the aisle measurement by the length of the seating areas, and the space the car in front of the doors, which is computed by multiplying (the width of the car) x (the width of the doors) x (the number of doors [sic. should be “number of doors on one side”]).[10]

The usable standing space for the R62, A Division cars, using such calculations, was said to be 208 square feet. The scheduled minimum space per standee was 3.0 square feet. (The observed minimum square feet per standee was reported to be 2.9.)

The 1988 Guidelines “provide for scheduling 110 passengers per car for the ‘A’ division 51 foot car” during peak periods,[11] essentially the same space per standee of 3.0 square feet as had been the previous, unofficial standard.[12]

Understanding the Loading Guidelines

A better understanding of the NYC Transit loading guidelines can be obtained by study of the book by John J. Fruin, “Pedestrian planning and design,” first published in 1971.[13] It is cited and quoted in the Technical Appendix to the NYC Transit Guidelines.[14]

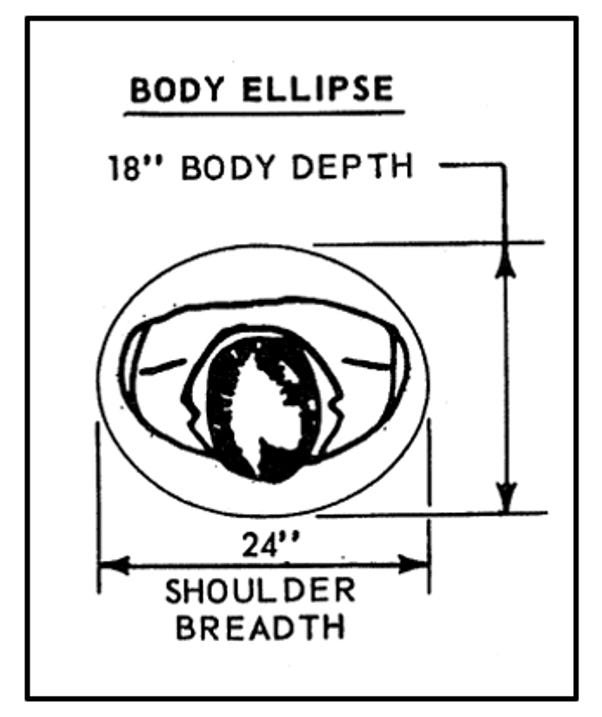

Fruin’s discussions of personal space are the based on the Body Ellipse of an adult male (shown below).

Fruin noted that “An 18 by 24 inch body ellipse, equivalent to the area of 2.3 square feet, has been used to determine the practical standing capacity of New York City subway cars. A U.S. Army human factors design manual also recommends the use of these dimensions.[15] Fruin apparently did his research in the 1960s. Given the growth in body sizes since then, I estimate that the appropriate body ellipse dimensions today would be 20 by 26.4 inches, approximately a 10% increase in each horizontal direction, which I refer to as the “Expanded Body Ellipse.” (See below).

Fruin did not directly address standing space in subway cars; however, the Technical Appendix to the NYC Transit Guidelines referred to Fruin’s levels of crowding in a waiting line as applicable to evaluating the amount of floor space to be allowed for standing subway passengers, saying:

Level D allows each person 3-7 sq' of standing space and is described as

allowing restricted movement without touching another person. According to

psychological experiments cited by Fruin, this level of service "is not

recommended for long-term periods". Level E allows 2-3 sq' per person and is

described as a "touch zone" level of service. At this level you cannot avoid

touching the person next to you and is recommended for very short periods of

time i.e. elevator rides. Level F allows 2 sq' or less of space per standee

and no movement is possible. This level of service can create a panic

situation and causes the standee "physical and psychological discomfort".[16]

Fruin’s “Personal Comfort Level” diagram is reproduced below.[17] Note that each person’s zone is circular, rather than an ellipse. That is consistent with wanting more space in front of your face than—for example—adjacent your shoulders. When the Expanded Body Ellipse is used, instead of Fruin’s Body Ellipse dimensions, the space allocated to each rider at a “Personal Comfort Level” would expand to a 23.4” radius.

Fruin’s “No Touch Zone” diagram is reproduced below.[18] At this level, with the Expanded Body Ellipse, the space allocated to each rider would have a 20.4” radius.

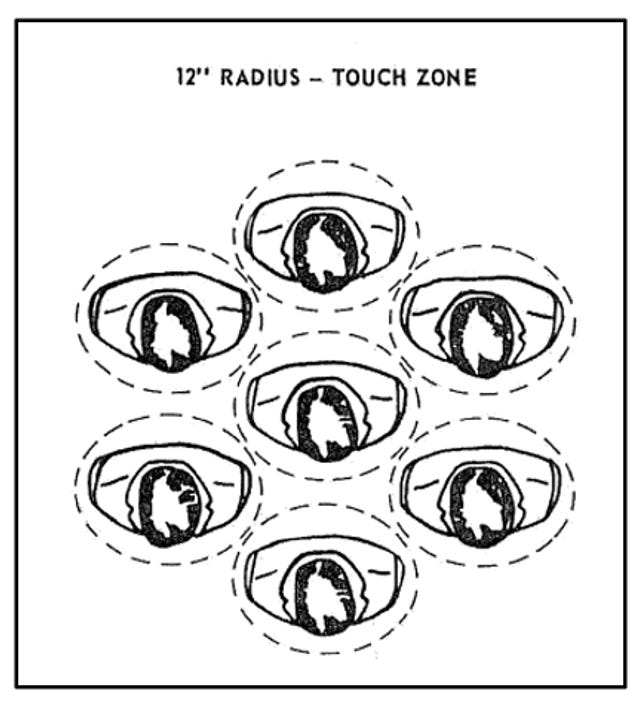

Fruin’s “Touch Zone” diagram is reproduced below.[19] This level was recommended only for very short periods of time, such as an elevator ride. At this level, with the Expanded Body Ellipse, the space allocated to each rider would have a 14.4” radius.

The Table below summarizes the radii and approximate areas occupied with Fruin’s Body Ellipse and the Expanded Body Ellipse at the “Touching” level.

Note that, while the radius of the space occupied only increased 10%, the area occupied at the “Touching” level of crowding increased 22.6%. If there are 208 square feet available in Division A railcars for standees, as suggested in the current Guidelines as discussed above, and if each standee is granted 3.8 square feet of space, such cars would appear to accommodate only 55 standees, and a total of 95 riders (not the current Guidelines’ total of 110).

The goal of providing at least 3.0 square feet per rider, specified in the current, long-standing NYC Transit Guidelines, is no longer adequate space for reasonable rider comfort. The Guidelines have not been revised to reflect the physical size of current riders. The Guidelines should be revised.

This article expresses the personal views of the author and does not express the views of his employer, or any client or organization. The author has degrees in law and physics, and has taken several engineering courses. After five years of work as an engineer, he has practiced law primarily in the field of patents for over 50 years, dealing with a wide variety of technologies. He is a life-long railfan and user of public transportation in the United States, Europe and Japan.

As usual a PDF copy of this article is attached.

[1] © John Pegram 2025.

[2] Fruin, Pedestrian planning and design, pp. 64-65 (1971). Hereinafter cited as “Fruin.” Citations here are to the 1987 revision, published by Elevator World, Inc.

[3] Data from CDC, “Mean Body Weight, Height, and Body Mass Index, United States 1960–2002 (Feb. 2004) (hereinafter “CDC 2004”), Table 6, and CDC, “Anthropometric Reference Data for Children and Adults: United States, 2015–2018” (Jan. 2021) (hereinafter “CDC 2021”), Table 6.

[4] CDC 2021, supra note 3, Table 6.

[5] CDC 2004, supra note 3, p. 1.

[6] Data from CDC 2004, Table 10 and CDC 2021, Table 14, both supra note 3.

[7] CDC, “Obesity and Severe Obesity Prevalence in Adults: United States, August 2021–August 2023” (Sept. 2024) (hereinafter “CDC 2024”).

[8] NYC Transit, “Rapid Transit Loading Guidelines,” (herein “Guidelines”).

[9] Guidelines, p. 2.

[10] Guidelines, Technical Appendix, p. 3.

[11] Guidelines, p. 2.

[12] Guidelines, Technical Appendix, p. 3.

[13] Supra, note 2.

[14] Guidelines, Technical Appendix, p. 1.

[15] Fruin, p. 20

[16] Guidelines Technical Appendix, p. 1.

[17] Fruin, pp. 66, 68.

[18] Fruin, pp. 66-67

[19] Id.